A Brief Introduction to Exoplanets

The key to finding life elsewhere in the galaxy.

Contents

Need a refresher on solar systems, galaxies, and the universe?

Read Space 101.

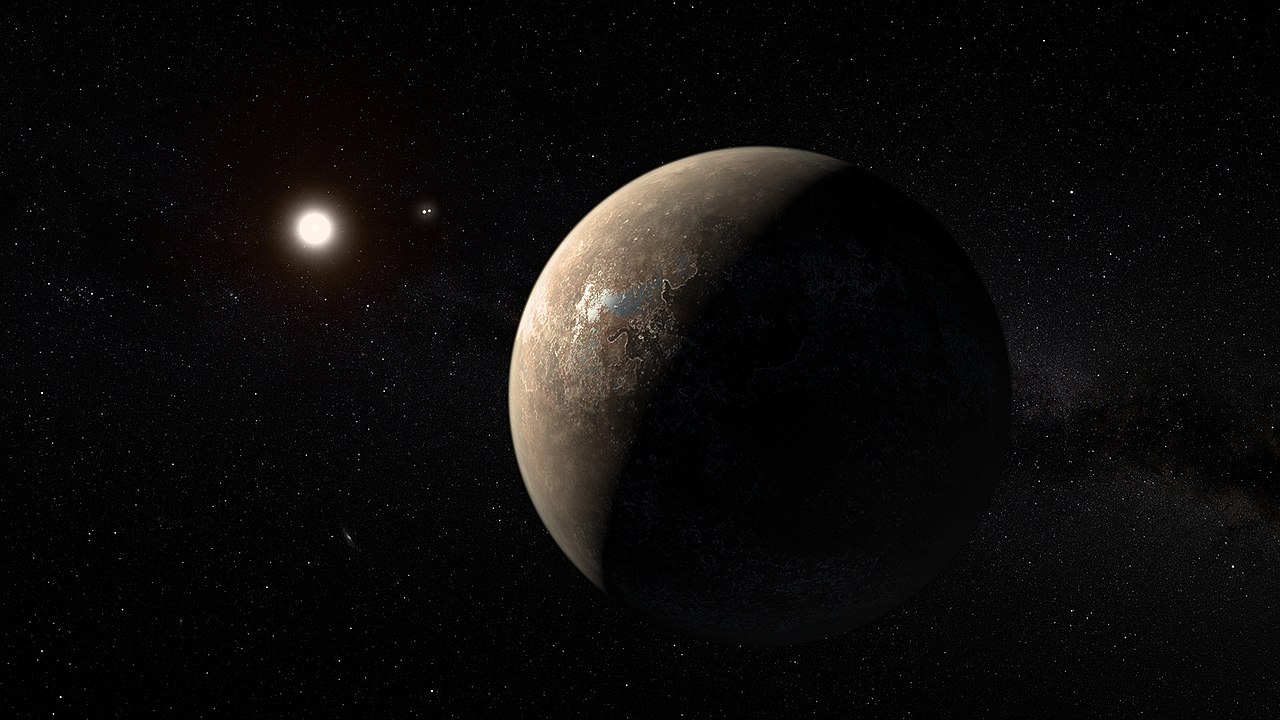

Exoplanets are planets that exist outside of our solar system. We find them trillions of kilometers away, orbiting distant stars in solar systems of their own. The closest exoplanet to Earth, Proxima Centauri b, is so far away that light emitted from the star it orbits takes over four years to travel through space and reach us here on Earth.

Although they're a long way away, astrophysicists have developed techniques to help us detect, analyse, and understand the characteristics of thousands of exoplanets in the Milky Way. We can even predict the weather on some of them!

Exoplanets are the key to answering many big questions about the universe, including the question of whether or not the lifeforms on Earth are alone in the universe... We'll take a look below at how astrophysicists manage to study these extraordinary planets.

Introducing Exoplanets

An exoplanet is a planet that orbits any star other than the Sun – and over 4,000 of them have now been discovered. Scientists nowadays are not only able to find these amazing planetary systems, but can even use space telescopes to start to understand the weather on these alien worlds! This next video features two astrophysics from the University of Exeter, who explain what exoplanets are in more detail, the different types of exoplanet, and where we find them.

Only three different types of planet occur in our solar system: rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars), gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), and ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). In contrast, there are many different types of exoplanet, most of which don't occur within our solar system. Some examples include: Hot Jupiters which are similar to Jupiter, but orbit very close to their star, so they're extremely hot; cotton candy planets, which have extremely low densities; or Super Earths, which are rocky planets similar to Earth, but larger and much denser.

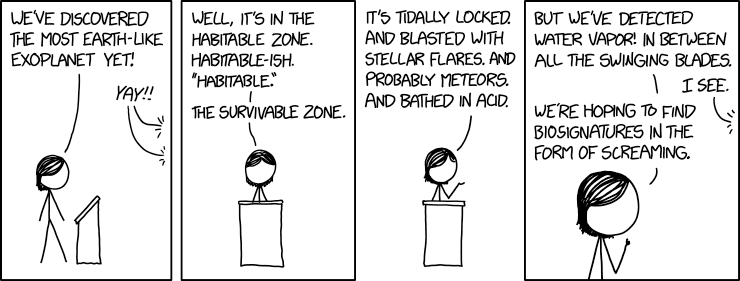

The planets of most interest to us are those that orbit within the habitable zone of their star. The habital zone is a particular range of a distances from a star, where the temperature on the planet is such that liquid water could exist. These planets are the best candidates for hosting life. We'll talk more about habital zones in the section on exploring exoplanets.

What would it be like to stand on the surface of another planet? Thanks to virtual reality, we can take a tour to six known exoplanets and explore their characteristics. In this next video, atrophysics from the University of Exeter Dr.Elisabeth Matthews, Prof. David Sing, Dr. Stefan Lines, Dr. Nathan Mayne, and Dr. Jessica Spake give a guided tour of what it would be like to visit these exotic worlds, and explore them in high definition and in 3D. Once the video is playing, click and drag to explore the surroundings.

As you'll see, exoplanets can be pretty inhospitable places!

Questions about exoplanets

- Prof. David Sing talks about earth-like exoplanets that are a similar size to the earth, but many times more massive. More massive means more mass. How can that be?

- Describe the properties of some of the most common types of exoplanets that have been detected.

Detecting Exoplanets

There are many methods by which we can detect exoplanets.

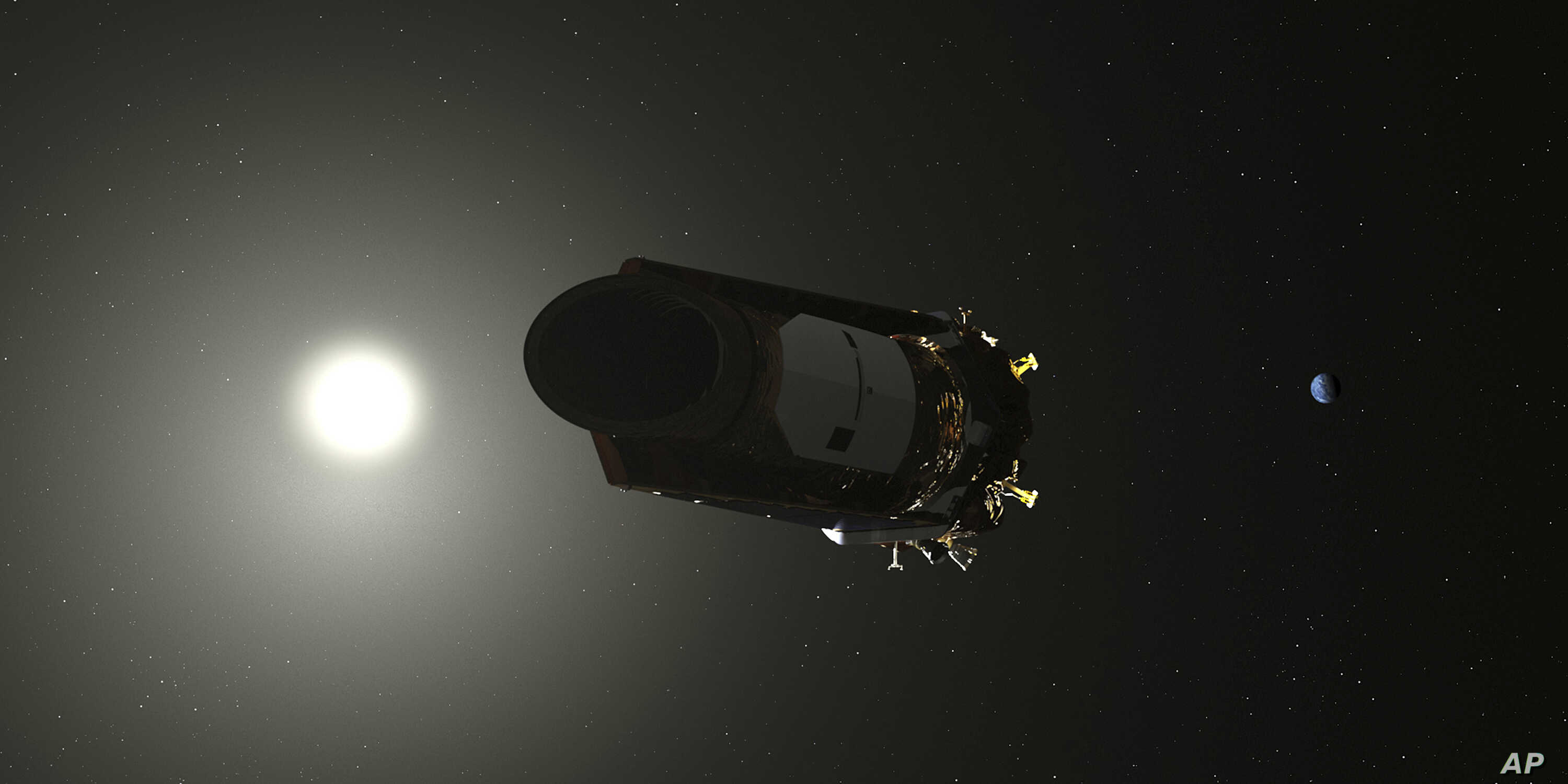

Each method involves using telescopes, either based here on Earth in observatories, or in space, orbiting Earth. The most famous satellite telescope is the Hubble Space Telescope, which went into orbit in 1990 and is still operational today. In 2006 the Hubble Space Telescope was used to survey stars, searching for exoplanets, in a project called SWEEPS. SWEEPS discovered 16 candidate planets, which sounds like a lot, but more recently the Kepler Space Telescope discovered around 2300 new exoplanets between 2009 and 2015.

Part of the reason for the Kepler mission's success was that scientists managed to invent new methods of detecting exoplanets while the telescope was in orbit. This is because exoplanet detection relies on the analysis of data recorded by sensors within the telescope, not on images captured. In fact, it's extremly rare to directly view an exoplanet, with only around 1% of exoplanets being discovered this way. Discovering exoplanets via direct imaging is difficult because exoplanets are extremely faint light sources compared to stars, and what little light comes from them tends to be lost in the glare from their parent star.

Let's take a look in more detail at the two most common methods used to detect exoplanets.

The radial velocity technique

The radial velocity technique is also known as the 'Doppler wobble' technique. In this method, the explanet itself is not directly detected. Instead, the technique relies on the effects of gravity – just as the star is exerting a gravitational force on the planet, the planet is also exerting a gravitational force on the star (remember Newton's third law!). This causes the star to 'wobble' slightly as it spins, and using very sensitive telescopes we can observe the slight wobble of the star.

This was the first technique used to detect an exoplanet.

In fact, rather than just wobbling, the star and the planet form a system, and are both orbiting around the centre of mass of the system, known as the barycenter. Because the star is many times more massive than the planet, the barycenter is very close to the centre of gravity of the star. As such, the star only moves slightly, and appears to wobble, while the planet orbits much further away from the centre of mass.

In this simple animation, there is only one planet affecting the system, but in practice, most stars will be orbited by more than one planet. Each of these planets will exert a force on the star proportional to its mass, and this affects the way the star wobbles. In practice this means that the wobble is slightly reduced, making it extremely difficult to detect, and requiring highly sensitive telescopes to make these observations.

The transit method

The transit method is a much simpler concept than the radial velocity technique. The method works by looking for regular dips in the brightness of a star as a large planet passes, or transits, in front of it. For close-orbiting giant planets, this dip in brightness can be as much as 2% of the original brightness, and occurs every few days.

The transit method has detected by far the highest number of exoplanets. By scanning large areas of the sky containing thousands or even hundreds of thousands of stars at once, transit surveys can find more extrasolar planets than the radial velocity method.

The transit method has two major disadvantages. First, planetary transits are observable only when the planet's orbit happens to be perfectly aligned from the astronomers' vantage point. The probability of a planetary orbital plane being directly on the line-of-sight to a star is the ratio of the diameter of the star to the diameter of the orbit (in small stars, the radius of the planet is also an important factor). About 10% of planets with small orbits have such an alignment, and the fraction decreases for planets with larger orbits. For a planet orbiting a Sun-sized star at 1 AU, the probability of a random alignment producing a transit is 0.47%. Therefore, the method cannot guarantee that any particular star is not a host to planets.

The second disadvantage of this method is a high rate of false detections. A 2012 study found that the rate of false positives for transits observed by the Kepler mission could be as high as 40% in single-planet systems. For this reason, a star with a single transit detection requires additional confirmation, typically from the radial-velocity method. The radial velocity method is especially necessary for Jupiter-sized or larger planets, as objects of that size encompass not only planets, but also brown dwarfs and even small stars.

So, now we know how expolanets are detected – but that's only half of the story? How do we know what these exoplanets are like? How do we know their temperature, their composition, and even their weather? We'll take a look at how we explore exoplanets in the next section.

Questions about detecting exoplanets

-

Look at this graph [Graph A] showing the number of exoplanets detected by different methods each year, up to 2011.

Now take a look at this graph [Graph B], which is an updated version.

- Identify a trend in the data that shows which method of detection has been most successful over time.

- Suggest an explaination for this trend.

Exploring Exoplanets: The search for life

As well as attempting to detect new exoplanets, astrophysicists can understand the composition, structure, and even the weather on known exoplanets. This can be done by analysing data about the planet gathered by making observations using the different wavelengths of light, and comparing the measurements to sophisticated computer models.

Hold on a second... Didn't we say before that sometimes astrophysicists detect exoplanets without even being able to see them? If we can't even see them, how could we possibly understand the weather on exoplanets?!

As Dr. Nathan Mayne explains [Figure 16], the weather on Earth is largely dictated by large scale differences in temperature. At the equator, the temperature is hotter, causing air to rise. At the poles, the temperature is much colder, causing air to sink towards the surface. This difference in temperature between the equator and the poles is called a temperature gradient, and creates a convection current as warm air rises and cool air is drawn in to replace it. This movement of air is what we commonly call wind.

The same principles can be applied to exoplanets. If we know how hot a distant star is by measuring its brightness, and we know how far away its orbiting planet is, we can start to calculate the temperature on the surface of the planet. For some planets, we can also calculate the temperature differences between the equator and poles. For tidally locked planets, we can calculate the difference in temperature between the night and the day sides. In each of these cases, knowing the temperature difference helps us understand the winds on the surface of the planet, and therefore the larger scale weather patterns that make up its climate.

The discipline of analysing the climate on distant exoplanets is known as exoclimatology.

Of course, this concept only works for planets with an atmosphere. Some planets, such as Mercury in our solar system, have either a very thin atmosphere, or no atmosphere at all. No atmosphere means no weather!

Exoplanets: The homes of alien lifeforms?

Exoplanets hold the clues to life elsewhere in the galaxy! Watch the video in Figure 18, of Dr. Nathan Mayne explaining how he's building a framework to use exoclimatology to search distant solar systems for signs of life. The models that make up the framework help us determine the liklihood of an exoplanet hosting forms of life. Once we've established the possiblity is there, we can start attempting to detect biosignatures — evidence of past or present lifeforms.

As we mentioned earlier, our our search for life elsewhere in the universe is focused on Earth-like planets in the habitable zones of distant stars.

Two key features of an Earth-like exoplanets are that they might have liquid water on the surface of the planet, and an atmosphere that could support life as we know it. Of course, life on other worlds might not need the same conditions that lifeforms here on Earth require, but these constraints are a useful starting point.

It’s important to distinguish 'Earth-like' from 'Earth-sized' when discussing exoplanets. Earth-like is much more important than Earth-sized – just because a planet is a smiliar size to Earth, it doesn’t mean that it could support life. Here in our solar system, Venus is a similar size to Earth, but it has no surface water, an atmosphere of almost pure carbon dioxide, and an average surface temperature of nearly 500°c! These aren't the kind of conditions we'd expect life to exist in.

So how do we look for Earth-like planets? The most basic condition for being able to sustain liquid water is the planet’s position in relation to its star. Scientists call the region around a star where liquid water can exist on the surface of a planet the habitable zone: not so close to the star that water all evaporates, and not so far from the star that it all freezes. This area is also known as the 'Goldilocks zone', because it's not too hot, and not too cold.

We can tell if a planet is in the habitable zone based on the distance of the planet from its host star and the temperature of that star. A bigger, hotter star’s habitable zone is farther out than that of a smaller, cooler star.

There could be as many as 40 billion planets in the habitable zone of stars right here in the Milky Way galaxy. So far we’ve found about 200. That may not seem like many, but consider this: it's possible we’ve already found a planet that hosts life, and we just haven't realised it yet...

Cinematic exploration:

Questions about exploring exoplanets

- Explain what we mean when we say that say that a planet is 'tidally locked' to its star (hint: use Figure 16).

Meet the Astrophysicist

Science and scientists

Robbie Ridgway is second year PhD student. Originally from Scotland, Robbie lived and studied in Canada before coming to the University of Exeter. In this interview, with Professor Justin Dillon, Robbie explains why he became a PhD student, what his work involves and how his branch of science makes new knowledge.

The interview lasts 16 minutes. Watch it and then think about these questions.

Questions about being a scientist

- Which personal characteristics would be useful for someone carrying out this kind of research?

- What is it about Robbie’s work that makes it “scientific”?

- How might Robbie’s work be useful to the general public?

More on Exoplanets

This has been a good introduction to exoplanets: how we find them, and what we can learn about them, why they're important. But so far, we've barely scratched the surface!

The internet is awash with great information about exoplanets. We've pulled together some of our favourite videos, articles, and simulations.

Learn more about exoplanets.

Need a refresher on solar systems, galaxies, and the universe?

Read Space 101.

Footnotes and References

Previous: Space 101

Up next: Exoplanets II

Compiled by Sam Mead and Ollie Rowlands from the University of Exeter Physics PGCE Course.